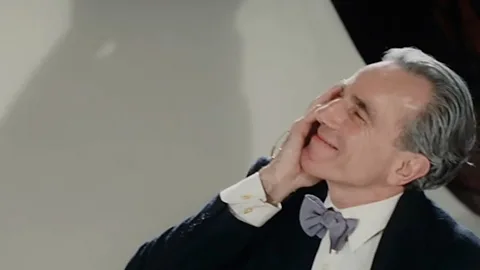

Phantom Thread: Five stars for Day-Lewis’s final film

Focus Features

Focus FeaturesThe actor says Phantom Thread will be his last performance. If he holds true to that, this is an incredible parting statement, writes critic Caryn James.

At the start of Phantom Thread, Daniel Day-Lewis meticulously goes through a morning ritual as Reynolds Woodcock, a 1950s London fashion designer. With extreme precision, he polishes his shoes, brushes back his mane of grey hair, applies a bit of makeup to his cheeks. Each gesture reveals how ideal the casting is: a perfectionist playing a perfectionist.

The scene also signals that while Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film may be set in the fashion world, it is not really about clothes. Visually sumptuous though it is, this is a brilliantly nuanced, psychologically complex story about obsession, love, control and surrender, all cloaked in a sophisticated Gothic romance. In the best sense, Phantom Thread is Alfred Hitchcock meets Henry James.

The territory is new to Anderson, known for brash, California-set movies going back to Boogie Nights. But he establishes Woodcock’s world with effortless grace. Piano music echoes the 50s without sounding retro (the standard My Foolish Heart is used as an instrumental theme). The camera glides and takes us inside the elegant Georgian townhouse where Woodcock works and lives with his sister and business partner, Cyril (Lesley Manville).

Theirs is a most peculiar relationship. Cyril’s staring gaze and severity recalls Mrs Danvers in Hitchcock’s Rebecca, but Manville makes her more humane, devoted to her brother. Her tailored dark dresses keep her in the background, while he clothes a countess in mauve velvet and silk. (The dress “will give me courage,” says the unhappy countess, in a nod to the true value of Reynolds’ work.) Cyril exerts her own fierce control, though. When Reynolds tires of the latest woman he has brought into the house as his lover, Cyril volunteers to tell her it’s time to go.

Reynolds affectionately calls his sister “my old so-and-so,” the kind of comfy endearment you might expect from a long-married couple. With exquisite balance, Day-Lewis, Manville and Anderson allow us to notice the oddity without suggesting anything more than an intense emotional bond.

Reynolds is, after all, strangely attached to his family. He has a lock of his dead mother’s hair sewn into the lining of his jacket so she will always be near his heart. When he feels that their mother is observing them, he calmly tells Cyril, “It’s comforting to think the dead are watching over the living. I don’t find that spooky at all.” There are no unnatural apparitions except in a moment of fevered delirium, but Phantom Thread carries the haunted emotions of a ghost story.

In his remarkable, astute performance, Day-Lewis makes his character idiosyncratic yet entirely believable. Reynolds is supremely confident in his talent and worth, politely imperious, and surrounded by staff and clients who all but genuflect to him. Yet, like Manville, Day-Lewis avoids any hint of caricature.

Nothing in Reynolds’s rigid life prepares him for Alma (Vicky Krieps) a modest, lovely waitress of vague European origin, who serves him breakfast at a country inn. After he takes her to dinner - wiping off her lipstick and already beginning to transform her to his taste – they return to his country house and a sly seduction scene. Or is it? Where the London townhouse is full of marble floors and sun-filled windows, the country house is a dark cottage. In Reynolds’ workroom, Alma takes off her dress. He drapes fabric over her shoulder to begin a design and -- to say more would reveal too much, but this scene is so typical of the film’s wit and surprising turns that we can’t be entirely sure what Reynolds was up to in the first place.

A finely woven thread

Even after Alma moves into the townhouse as Reynolds’ model and muse, their relationship remains mysterious. In pure 50’s fashion, there is no sex scene. Her bedroom is adjacent to his and we’re left to speculate. Krieps brings just the right touch of self-effacement to Alma, who acquiesces as Reynolds reinvents her. And when it turns out that she has a mind and will of her own, Krieps makes the change one of degree, the response of a frustrated lover. “Maybe I like my own taste,” she tells Reynolds.

The power struggle among the three characters begins in earnest in the film’s second half. And as in Henry James’s novels, the calm surface of life conceals an intricate web of profound love, enigmatic motives and manipulation.

The film becomes more dramatic and a touch magical, as Reynolds tells Alma he needs her to “break a curse” that has kept him in his cocoon for years. That does not necessarily forecast a fairy tale ending.

Every aspect of the film meshes with Anderson’s elegant aesthetic and delicate changes in tone. Jonny Greenwood’s score, ranging from those 50s melodies to Debussy and Schubert, enhances and evokes each scene’s mood without ever becoming intrusive. Mark Bridges’ costumes create a signature hourglass style for the house of Woodcock. The uncredited cinematographer is Anderson himself. He lets the camera roam when he feels like it, following a line of seamstresses as they arrive for work and ascend a spiral staircase in the townhouse. More often he stands back and slowly zooms into a scene, quietly guiding our eyes.

But his screenplay and direction are what make the film unique. With a sure hand, he drops bits of comic relief into the emotional turmoil. There is tension at the Woodcock breakfast table due to loud buttering of toast. In one scene Alma and Reynolds insist on removing one of his dresses from a drunken, sleeping American because she doesn’t deserve to wear it. (Also, she wiped her mouth on the collar.) The aftermath of the scene makes it clear that they both got an erotic charge from their shared defense of his creation. And Anderson knows when to let the actors’ silent glances speak for them.

The Master, another Anderson film about obsession and willfulness, went as haywire as its outsized hero. Phantom Thread is beautifully controlled, even when the plot comes to include a wild New Year’s Eve party complete with a live elephant. A topsy-turvy psychological shift at the end feels more willed by Anderson than earned by the characters, but that is a minor flaw. The film’s ghostly title was inspired by a condition among Victorian seamstresses, who worked such long hours that afterwards they would see invisible threads before their eyes. The layered meanings are just right for a film that is rooted in reality, becomes fanciful, and unveils more of its richness with every viewing.

★★★★★

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.