Was 1999 cinema’s last great year?

Alamy

Alamy20 years on, it is seen as a high watermark for Hollywood, which hasn’t been matched since. But is that a fair assessment or false nostalgia? Two writers offer contrasting takes.

Two decades ago, Hollywood had a golden run of films which has subsequently seen some critics laud it as cinema’s greatest year – and others declare it to be the last great year. Indeed, such is the discussion 1999 inspires, it will be the topic of a special event next week as part of the Film4 outdoor Summer Screen season at London’s Somerset House. In the meantime, we asked two writers to battle it out over whether it truly deserves its peerless reputation:

Yes, writes Nicholas Barber

Apart from being on a pub-quiz team when it’s time to name all of The Magnificent Seven, the most nerve-racking moment for any film journalist is when someone asks you what to see at the cinema on a Saturday night.

I know, I know, it shouldn’t be a problem. If you watch several films a week as a part of your job, it should be a doddle to pick two or three which are worth the price of a multiplex ticket. But instead you find yourself thinking, well, X is good, but it’s a tiny foreign-language character study that’s been out for a fortnight, so it’s probably disappeared already. I’ve got to come up with something that might actually be showing within a 10-mile radius. And, invariably, you end up mumbling, “Um... the latest Spider-Man is OK.” Pathetic, isn’t it?

Alamy

AlamyIt must have been easier 20 years ago. If you were asked for a recommendation in 1999, you could have droned on for hours about the rise of 'Indiewood', about the DVD boom which was encouraging studios to fund offbeat projects with cult potential, about the new wave of smart and geeky writer-directors redefining mainstream cinema, about the innovative films which had generous budgets and A-list stars, but which were as literate and adventurous as anything being shown in an art house.

You could have mentioned Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman’s Being John Malkovich, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, David Fincher’s Fight Club, Alexander Payne’s Election, Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, M Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, David O Russell’s Three Kings, Mike Judge’s Office Space, and – astonishingly – a lot more besides. These were films so distinctive, intelligent and downright fun that you wouldn’t just recommend them: you’d push people into the cinema, and then wait outside so you could discuss all the provocative themes and stylistic flourishes afterwards.

That list is evidence enough that 1999 was a cinematic year that has never been bettered – and never will be. And yet its emerging generation of super-talented and super-confident US auteurs wasn’t the whole story. Along with all the new-ish kids on the block, established directors were releasing films which weren’t all acclaimed at the time, but which have come to be treasured: Michael Mann’s The Insider, Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, David Lynch’s The Straight Story, Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam, Mike Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy, David Cronenberg’s Existenz, Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog : The Way of the Samurai, Milos Forman’s Man on the Moon, Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow.

Alamy

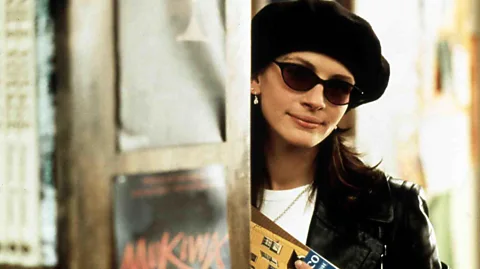

AlamyMeanwhile, megastars-to-be Gwyneth Paltrow and Cate Blanchett were being showcased in Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley, and another British director, Sam Mendes, immediately made himself top Hollywood property with his film debut American Beauty. Wim Wenders’ Cuban music documentary, Buena Vista Social Club, was a sensation. And genre movies – thrillers, romantic comedies, family cartoons and horror movies – weren’t doing too badly, either. 1999 was the year of The Thomas Crown Affair, The Mummy, Notting Hill, Bowfinger, American Pie, Drop Dead Gorgeous, 10 Things I Hate About You, Toy Story 2, The Iron Giant and The Blair Witch Project.

If you look closely enough, you can spot a couple of remakes and a sequel on that mouthwatering menu, but what unites almost all of the films cited above – aside from how terrific they are – is that they weren’t reheating a concept that had been served up already, again and again. They were original. How times have changed.

In the 21st Century, streaming platforms have made the small screen the home of fresh ideas, as well as for conversation-starting communal cultural experiences. As for cinema, it appears that it caught a virulent strain of the millennium bug. If 1999 was the year when everything went right, it might also have been the year when everything began to go wrong.

The release of Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace proved that long-dormant series could be lucratively revived. Toy Story 2, the first ever Pixar sequel, proved that cartoon follow-ups needn’t be straight-to-video cheapies, but major, money-spinning phenomena. The Matrix proved that digitally-enhanced superhero action could attract audiences of all ages. And The Blair Witch Project proved that found-footage horror in particular, and microbudget horror in general, could be a gold mine.

As wonderful as those films may have been – The Phantom Menace excepted, obviously – they taught Hollywood some toxic lessons. Instead of continuing to bet on young mavericks, studio executives twigged that there was a fortune to be made from superhero blockbusters, Disney sequels, merchandise-friendly franchises and cheapo horror movies. And that’s what we get in 2019, week after week. When someone asks what they should see at the cinema, it’s tempting to tell them to watch television instead. 1999 was the best of times, but it was the start of the worst of times, too.

Alamy

AlamyNo, writes Hannah Strong

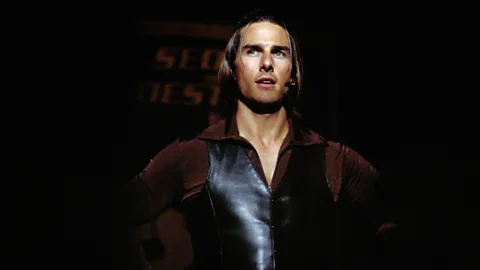

Waiting to take the stage of What Do Kids Know? in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 dramatic epic Magnolia, quiz show legend Jimmy Gator murmurs a quote from Bergen Evans’s 1946 book The Natural History of Nonsense: “We may be through with the past, but the past ain't through with us”. Magnolia is widely cited when cultural commentators wax lyrical about the delights of 1999: a year for cinema the likes of which have not been seen since. Evans’s quote seems more prescient than ever – the past ain’t through with us, and a sense of collective nostalgia sends us time-travelling again and again to 20 years ago, held up as a time filmmaking seemed more daring, inventive and ultimately transcendental than it is today.

Of course, 1999 was a banner year for filmmaking, predating the Hollywood obsession with remakes and reboots, superheroes and franchises as far as the eye can see. Up-and-coming filmmakers such as Paul Thomas Anderson, David Fincher, Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman created ground-breaking works which challenged audiences and are still widely loved, watched and debated today. Stanley Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, made its bow, while animation found critical and commercial success in Toy Story 2 and The Iron Giant. There’s no getting around 1999 as a great year for cinema, but to call it the last great year is to deny the great progress and radical changes that the industry has undergone since.

When we talk about 1999 in cinema, we talk largely about a canon of films made predominantly by white, male, middle- or upper-class US directors. Of course, there are exceptions to be found in Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (though with the Coppola name privilege is unavoidable) and in The Wachowskis’ The Matrix or M Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, but by and large, the films we cite today as modern classics from 1999 are not representative of the world we live in, or indeed the world as it was even that year. There are few women, few people of colour, and few LGBTQ filmmakers and stories amid the fabled class of 99, and the films that did represent these voices, such as Jamie Babitt’s But I’m A Cheerleader, Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry, or Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher, did not make bonafide superstars of their directors in the same way the likes of Fight Club or Being John Malkovich did.

“They don’t make ‘em like they used to,” comes the withering refrain when discussing film history. But is that always a bad thing? The film industry has been built on imbalances of power, be they according to gender, racial, or sexuality – increasingly it feels as if we are moving to a place where the stories we are seeing on screen are more representative of the people that live in the world. Directors such as Ava DuVernay, Barry Jenkins, Jordan Peele and Nadine Labaki all represent the future we are moving towards, challenging preconceptions about genre, form, and what the purpose of cinema is.

Alamy

AlamyTo highlight that 1999 was not the last great year, you only need to look back at 2017, which gave us Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me By Your Name, Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water, Jordan Peele's Get Out and Greta Gerwig's Lady Bird to name but a few titles. Even so far in 2019 films such as Us and Booksmart have proven the appetite for original storytelling, while at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, Mati Diop’s Atlantique and Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire all confirmed that mainstream British and US film is not the last bastion of great cinema.

Nostalgia is often the enemy of progress when it comes to pop culture. We have a tendency to look back fondly on what came before, ironing out the flaws in our memory until the past is something that seems truly great, and even aspirational. But ironically this habit of looking backwards is the same impulse that has helped usher in the age of live-action remakes and never-ending franchises that cinema nostalgists often complain about; there is a belief that audiences want familiarity over the unknown. Although the highest grossing films at the box office nowadays are invariably Disney and Marvel titles, and big studios could certainly stand to take more chances on the films and filmmakers they champion, that doesn’t mean that filmmaking itself doesn’t continue to push the boundaries.

We’re spoilt for choice between the plethora of streaming services and weeks where upwards of five new films are released in cinemas; the problem is, it’s often hard to know where to start, and audiences have to look harder to find great cinema. The past ain’t through with us, but we’ve still got the present and future. The talent is there, and the appetite too: it’s complacency which threatens to kill creativity.