'It didn't express the real horror': The true story of The Great Escape

Alamy

AlamyOn 24 March 1944, 76 allied officers broke out of a German prisoner-of-war camp, Stalag Luft III – a mission that was memorialised in a classic film, The Great Escape. In 1977, a key member of the escape team, Ley Kenyon, was interviewed on the BBC's Nationwide.

On a snowy moonless night in 1944, more than 200 allied officers attempted to break out of a German prisoner-of-war camp. It was the culmination of an incredibly ambitious plan that entailed more than a year of bribes, tunnelling, and the assembly-line production of equipment, uniforms and documents, all of which had to be painstakingly hidden from the camp's guards and spies.

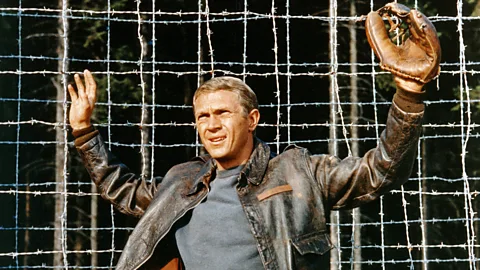

The Great Escape, John Sturges's 1963 film about the breakout, is a much-loved classic starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and James Garner. But it contains many inaccuracies. Jem Duducu, historian and presenter of the Condensed History podcast, described it in an interview in Metro as "a strange mixture of fastidious creation and pure Hollywood fantasy".

The story was first told by Paul Brickhill, one of the people who helped with the escape attempt, in his 1950 book, The Great Escape. He describes Ley Kenyon, who illustrated the book, as the mission's "star counterfeiter". Discussing the film with Dilys Morgan on the BBC's Nationwide in 1977, Kenyon said: "It was good entertainment, but it certainly didn't express the real horror of being a prisoner of war, the horror being, of course, in one's personal feelings about being behind barbed wire – the boredom, the hunger. The hunger was pretty grim."

Other ex-prisoners had a different view of the film. Charles Clarke, who was in the camp at the time, and had aided the plot as a look-out, told the BBC in a 2019 radio interview: "Even after all these years, I've always thought what a remarkable film it was."

One major change that the film made was to the personnel involved. While the events of The Great Escape are mostly rooted in fact, names were changed, and various people were combined into composite characters. At the time of the escape, no Americans remained in the compound, and the man who was said to be the model for McQueen's Virgil Hilts, William Ash, did not take part. The plan was spearheaded by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell – who in the film was renamed Bartlett, and played by Attenborough. First captured in 1940 after being shot down, Bushell had an impressive record of escape attempts, once getting within 100 yards of neutral Switzerland.

Stalag Luft III was the Germans' attempt at an escape-proof camp, specifically for air force officers from the UK, Canada, Australia, Poland and other allied countries. It was built and run by the Luftwaffe as a secure place to hold people they believed were escape risks. What they had not done, however, was consider the ramifications of trapping so many escape experts in one place.

Months of preparation

The camp was built over sandy soil that was difficult to tunnel through. This subsoil was also lighter and more yellow than the dark topsoil, making it obvious if any appeared on the ground of the camp. Huts were perched on brick legs to make tunnels down from them obvious. Brickhill describes in his book a "double barbed wire fence nine-feet (2.75m) high", just outside of which were 15-ft (4.5m) high "goon-boxes" every 100 yards or so, manned by sentries with searchlights and machine-guns. Additionally, microphones were buried in the ground around the wire so that they could pick up the sounds of any tunnelling.

As you might expect from a plan hatched by soldiers, the tunnel-digging enterprise was run with military efficiency. Bushell – also known as "Big X" – was in charge, and delegated certain parts of the organisation to other men. The planning began even before Stalag Luft III was built: Bushell and others knew it was coming, and volunteered to help build it. As a result, they were able to map it out and pick the best spots for a tunnel. Bushell had the idea that they would dig not one tunnel but three simultaneously. The logic was that if the Germans found one of them, they would never suspect that there were two others. They were to be referred to only by their codenames of Tom, Dick and Harry. Bushell threatened to court-martial anyone who even uttered the word "tunnel".

Alamy

AlamyThe aim was for 200 men to escape. This was a colossal undertaking. Each man needed a set of civilian clothes, forged es, a com, food, and more. Some es needed photographs, so a camera was smuggled in by a guard who had been bribed. In the film, Donald Pleasence's character is in charge of the forgery. In reality, Kenyon was one of the forgers who had to counterfeit the thousands of pieces of paperwork necessary. In the Nationwide interview, he recalled how they made it happen: "We made a printing press, for one thing, and each letter had to be hand-carved out of rubber which we got from the cobbler – rubber heels – or bits of wood cut with razor blades." Every document had to be perfect. They replicated es and paperwork that they had either stolen from the guards or persuaded the guards to show them. "Something like 7 or 8,000 pieces of paper were produced," he said.

The tunnels themselves were also miracles of engineering and ingenuity. An air pump was made with kit-bags and wood, and air was pumped through a line made of empty milk tins that had been sent by the Red Cross. A major issue was the dispersal of the soil that had been dug up, so bags that hung inside tros were fashioned from long underwear and used to drop the sand around the camp, where it could be kicked into the ground.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });