Terry Gilliam's Quixote: This 'cursed' film is finally here

Getty

GettyHe’s been trying to make an adaptation of Cervantes’ novel for over 20 years. After stunning setbacks, it’s about to make its debut, writes Nicholas Barber.

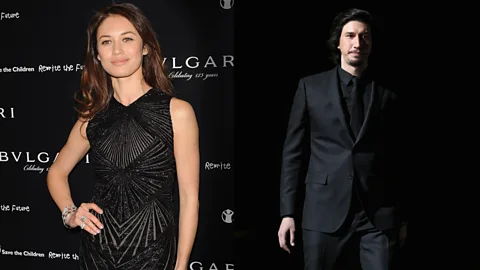

May 2017: in the forest of Valsain, 90 minutes’ drive from Madrid, Adam Driver is wading across a sparkling stream. On the far side, Olga Kurylenko, dressed in a long golden gown, is trotting through the evergreens on a white horse, followed by more actors on horseback, all in medieval garb. In front of them there are cameras, lights, smoke machines, catering vans, crowds of technicians and an illustrious director in a straw cowboy hat. To put it another way, if you were picturing what you wanted a film set to look like, it would be pretty close to this one.

But as beguiling as its combination of showbiz glamour, fairy-tale enchantment and workaday practicalities may be, the most thrilling aspect of this tableau is what’s missing. There are no meteorites, hurricanes or bolts of lighting. There are no ravenous tigers or cholera outbreaks. There isn’t an ambulance or a fire engine in sight. Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, a film which is synonymous with sustained and calamitous misfortune, is finally going without a hitch after nearly 30 years of blood, sweat, toil and tears.

“We’ve been very lucky,” says Gilliam, as Driver and Kurylenko get ready for their next take. He peers up at the sky through scrunched up eyes. “But I still worry. We’ve had too much luck, so it could go wrong at any moment. Today, the clouds are building. They’ll probably block out the light and we’ll have to go home.”

If only some inconvenient cloud cover were all that Gilliam had to worry about. A few weeks later, with the shooting wrapped, a Portuguese producer named Paolo Branco claims that the film is “patently illegal”. He bought the rights from Gilliam in 2016, he says, and so The Man Who Killed Don Quixote shouldn’t have been shot without his approval. Another producer, Peter Watson, argues that while Branco offered to invest in the film, he didn’t hand over any cash, thus negating his contract with Gilliam. “Senhor Branco’s interpretation of the law borders on the picaresque,” says Watson. “If he really wants to kill the venerable don, I suggest he takes up jousting.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Branco wouldn’t go away. Jump forward a year to the present day, and The Man Who Killed Don Quixote has been selected as the closing night film at the Cannes Film Festival. Gilliam’s dream project, decades in the making, was going to be seen at last. Or would it? Branco’s Paris-based company, Alfama, issued a writ against the festival, and asked the Paris District Court to ban the Cannes screening. “For legal reasons,” said a press release from the company, “this film cannot be exploited in any way without pre-agreement from Alfama Films Production.” The festival’s representatives responded that “Mr Branco has allowed his lawyer to use intimidation and defamatory statements, as derisory as they are ridiculous”. A French court dismissed the lawsuit on 9 May, a day after the festival opened, a bit of white-knuckle timing that probably doesn't surprise the 77-year-old Gilliam.

Alamy

AlamyIt is almost unbelievable that The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is still being wounded by the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. A previous doomed bid to shoot the film, back in 2000, is chronicled in Lost in La Mancha, an excruciatingly candid behind-the-scenes documentary. And even then, Gilliam had been wrestling with Don Quixote for longer than he cared to .

The impossible dream

Gilliam had the idea of a big-screen adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes’ landmark novel in 1989. (“And then I had to read the book,” he says.) He has never been able to forget the idea, partly because he and Quixote are kindred spirits. The two-volume novel, published in the early 1600s, features an ageing Spanish noblemen who has read so many stories about the age of chivalry that he comes to believe that he belongs there. Having cobbled together a ramshackle suit of armour, topped by a shaving bowl for a helmet, he recruits a portly peasant named Sancho Panza to be his squire, and sets off on a fanciful search for adventure. Most famously, Quixote charges at a windmill because he imagines it to be a giant, which is just the kind of thing that people do in Gilliam’s films.

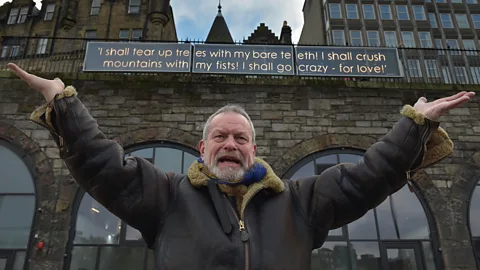

The first of these films was Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed with Terry Jones. It became a classic, voted 15th in BBC Culture’s 100 Greatest Comedies of All Time last year. Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1940, Gilliam grew up in Los Angeles, but he found fame in Britain in 1969 as the only American member of the Monty Python comedy troupe. His key contribution to the Pythons’ television shows was his surreal animated interludes, and since then the protagonists of many of his films, such as Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), The Fisher King (1991) and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009), have turned away from mundane reality and galloped off into worlds of magic and make-believe. That is, they have a lot in common with Cervantes’ deluded anti-hero. As for Gilliam himself, he doesn’t mind being compared to Quixote. “It’s true on too many levels,” he says with a weary grimace. “I don’t want to see the normal version of the world. I’ve always wanted there to be more play, more fun out there. And I suppose I’ve always thought that I was doing one thing, and discovered I was actually doing something else.”

Alamy

AlamyAs closely as he identifies with the Don, Gilliam quickly realised that it would be a mistake to try a literal translation of Cervantes’ 1,000-page doorstop. “The problem with all the other [screen] versions of Quixote,” he says, “is that people think you’ve got to be pure and faithful to what Cervantes wrote. No! You’ve got to be bold, play with it, step away from it, but let Cervantes be the inspiration.” His own concept was to see Quixote through contemporary eyes, so his script had a 21st-Century advertising executive called Toby Grisoni (named after Gilliam’s co-writer, Tony Grisoni) zipping back through time to 17th Century Spain, where Quixote mistakes him for the faithful Sancho Panza.

The screenplay attracted an ideal cast. Having starred in Gilliam’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), Johnny Depp signed up to play Toby. Quixote was to be played by Jean Rochefort, a 70-year-old French actor who had learnt English specifically for the role.

Alamy

AlamyBut even before the Lost in La Mancha documentary crew ed Gilliam at his base of operations in Madrid in August 2000, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote wasn’t going smoothly. Or, as Gilliam now puts it, “It didn’t have problems, it had one big monstrous problem.” Essentially, that problem was that he was aiming for the sort of star-studded fantasy extravaganza which would traditionally be backed by a Hollywood studio. But Gilliam was determined to make it in Europe with European money. Unfortunately, the first company to commit to the film, Working Title, got cold feet, and a German financier pulled out soon afterwards. The budget was slashed from $40 million to $32 million. While that still made The Man Who Killed Don Quixote one of the most expensive European films ever, it also meant that there was no margin for error. If Gilliam was to get it in the can, absolutely everything had to go according to plan. It didn’t.

Lost in La Mancha is painful to watch: an astonishing ‘un-making of’ documentary which defines the phrase ‘catalogue of disasters’. As Gilliam prepares to begin shooting, he finds that he can’t get his actors in the same place, or even in the same country, at the same time. Then he finds that the sound stage he has booked is actually an echoey, semi-derelict warehouse. His first assistant director, Philip Patterson, declares that the film is in “absolute and total disarray”. And that’s before the trouble really starts.

Alamy

AlamyOn the very first day of production, Gilliam and his team set up camp in a sandy nature reserve, its unspoilt plains and otherworldly rock formations making it perfect for a scene of Quixote riding through the desert. But there was one drawback. The nature reserve happened to be right next door to a Nato bombing range; whenever Gilliam tried to record some dialogue, a plane would roar deafeningly overhead.

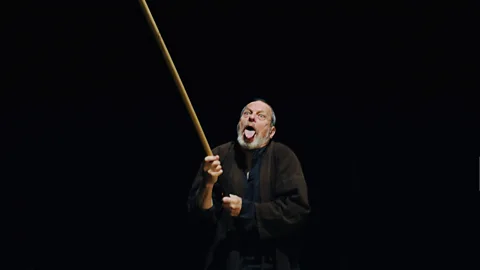

Day two was worse. After a sunny morning, clouds gathered, thunder rumbled and the film crew was battered by a cataclysmic deluge of rain and sugar cube-sized hailstones. In the circumstances, Gilliam decided that he might as well exult in the sheer glorious unjust madness of “this great Biblical storm”. A Lear-like figure, he dashed beneath a rocky overhang and peered out at the downpour. When he emerged, all of his equipment had been washed away in torrential rivers of mud.

The next two days were taken up with drying out props, and figuring out how to disguise the drastic change in the setting: the waterlogged sand was now a completely different colour from what it had been earlier in the week. And then, on the fifth day, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote almost became The Film That Killed Jean Rochefort. In Lost in La Mancha, the actor can be seen muttering his lines through gritted teeth, unable to hide how agonising it is for him sit on a horse and hold a lance. Shooting was suspended, and Rochefort flew back to Paris to see his doctor. The diagnosis: a double herniated disc.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven then, Gilliam pressed ahead with other scenes, but, with no way to tell when or if Rochefort would be well enough to get back in the saddle, insurers shut down the production. The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was dead.

Or so it seemed. Released in 2002, Lost in La Mancha closes with the following optimistic caption: “Six months later, Terry Gilliam began a new attempt to make the film.” But the process didn’t get any easier. “Every film I’ve done since then has been because I couldn’t get Quixote made,” says Gilliam. “So every time I finished a film, I’d start on Quixote again. And then another two, three years would go by, and I’d finally give up and get a proper job. But it’s never gone away.”

Back to La Mancha

Those proper jobs were no picnic, either. On The Brothers Grimm (2005), he clashed with the producers, the now-notorious Harvey and Bob Weinstein, who vetoed his casting choices and fired his long-time cinematographer, Nicola Pecorini. On The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, Heath Ledger died halfway through filming his lead role, forcing Gilliam to replace him in various sequences – ingeniously, but hardly satisfactorily – with Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law. And then there was his adaptation of Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s apocalyptic comic novel, Good Omens. Gilliam co-wrote a screenplay, cast Depp and Robin Williams as its main characters, and flew to Hollywood in 2001 to finalise a deal. Then came 9/11. All of a sudden, no studio was keen to make a boisterous comedy about the end of the world.

In between these stressful enterprises, there were regular announcements that Quixote would ride again. In 2008, Depp was back as Toby, and Gilliam’s old Monty Python buddy, Michael Palin, was to play the Don. The next year, this double act was swapped for Ewan McGregor and Robert Duvall. But it was still tricky to raise the money required. “The film had become a legend,” sighs Gilliam, “and I think financiers don’t want to deal with legends, they want to deal with solid things. There was talk of a curse, the curse of Quixote. It’s absolute nonsense – but it made financiers very nervous.”

Still, there were some genuinely good omens in 2015. Amazon climbed aboard as one of the film’s backers, and the lead roles were ed to Jack O’Connell and John Hurt, who had the perfect face for Don Quixote. And then Hurt announced that he was undergoing treatment for pancreatic cancer, and he had to drop out. In 2016, he was replaced by the actor he had replaced, Michael Palin, and Gilliam found yet another Toby: Adam Driver.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Gilliam was still the movie business’s answer to Job, and the torments continued. In March 2016, it was reported that the film had a new producer: none other than Paolo Branco. The cameras were due to roll that September. But when Branco couldn’t raise his share of the finances, production was delayed again, and he tried to stop Gilliam making the film without him.

Nonetheless, by May 2017, shooting is well underway. “In the end,” says Gilliam, “we’re doing this for much less money than we honestly need. But everyone involved, from the cast to the crew, are all working their asses off for a fraction of what they would normally be paid, because they just want to see this thing done. It’s odd how being obsessive and not giving up can inspire other people to get involved. Fools that they are!”

Another small consolation for all the trials and tribulations he’s endured is that, at this point, Gilliam doesn’t believe that anyone else on the long list of almost-Quixotes could have matched the Quixote he ultimately got, Jonathan Pryce. The Welsh actor had played one of Gilliam’s trademark fantasists in his 1985 classic, Brazil, so there is something poetic about him playing such a character again now that he is 70 - the same age that Rochefort was when he had his go at the role.

“I have wiped most of the other attempts out of my memory, because it went on and on and on,” says Gilliam. “But along the way the cast just kept getting better and better. Jonathan has been wanting to [play Quixote] for 15 years – he’s been making my life a misery. And now he’s here and he’s just extraordinary. The editor, who is Spanish, says that she can never imagine another Quixote. So it’s as if the time was right: everything seemed to be ready to make this thing.” He squints up at the mostly-blue sky. “And even the weather agrees with us.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGilliam is not the only person who feels that the stars have aligned. Before her horse-riding scene, Kurylenko sits in the lunch tent, in full regal costume, and talks about seeing Lost in La Mancha. “You watch and you think, poor Terry,” she laughs. “Why does this have to happen to this wonderful man? He doesn’t deserve this. It’s just crazy. But it wasn’t meant to be, I guess. It wasn’t the moment. Now is the moment.”

Pryce is just as positive. “Obviously I’m glad [Gilliam] pursued it for my selfish reasons,” he says, having just shot a scene of his own. “And from what I can of the original script, this is an altogether better version. It’s a clearer story. Terry’s done a lot of rewrites – and he’s had a lot of time to do rewrites.”

The upshot of these revisions is that Toby is no longer transported back to the 17th Century: the reason why the actors are in historical costumes in today’s woodland scene is that the characters are having a fancy-dress party. In the current draft of the screenplay, the premise is that Toby revisits a Spanish village where he once made a student film of Don Quixote, and learns that the shoemaker he cast in the title role has been living as Quixote ever since. In other words, Pryce is playing a dreamer who is playing a dreamer, “I’m incorporating the idea of the damage that films do to people,” explains Gilliam, “so it’s become a bit more autobiographical.”

Sure enough, Gilliam seems slightly damaged himself when I meet him in Valsain. As effervescent and opinionated as he is, he is also stooped, gnome-ish and generally less manic than he appears in Lost in La Mancha. “I’m not as bouncy as I used to be,” he its. “I don’t have the madness and strength I used to have, so when things go wrong, when things are difficult, I’m more and more willing to give up.”

He also has doubts as to whether his film can possibly live up to the extraordinary mythology which has grown around it. “The problem is that people have very high expectations,” he says. “And a lot of people say I’m a fool to make the film, and that it would have been better to let people imagine how great it would have been, rather than making it a reality and disappointing them. People love Roman ruins because they’re not complete and you can imagine them. So I may be making a great mistake. Maybe the film would be better as a fantasy.”

So what keeps him going? “It’s a medical problem. It’s not a film, it’s a tumour, and I have to have it removed. I want it out of my life, frankly.”

That was in May, 2017. With the recent word that The Man Who Killed Quixote would be screened at Cannes, it looked as if the tumour would be removed, and the film he conceived in 1989 would be seen at last. But Branco’s latest legal threats changed the prognosis yet again. At last, we now know Gilliam, Driver, Pryce and Kurylenko will be on the red carpet on the festival’s closing day, Saturday 19 May. But when it comes to Quixote, you can never know for sure - Gilliam may have won the court ruling but it was also announced on 9 May that Amazon Studios has pulled out as Quixote's distributor in the US. It's hard to dispel an aura of gloom that's been hovering for so long. As I was typing this article, before the ruling came down, the director posted a link to a news story about Branco’s intervention on his Facebook page. “This is just to keep you loyal fans up to date,” wrote Gilliam. “I may need your help. I will let you know.”

[Editor's Note 9 May 2018: This story has been updated to reflect that Paolo Branco's lawsuit, which attempted to block The Man Who Killed Don Quixote from screening at Cannes, has been thrown out by a French court. The film will screen as planned 19 May as the festival's closing-night film.]

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.