Intimate images of a bathing beauty

Pierre Bonnard used stunning colour to depict moods and moments, both happy and melancholic. Cath Pound explores the vibrant work of the shy French artist.

The US critic Jed Perl once referred to Bonnard as “the most idiosyncratic of all the great 20th-Century painters”. His highly original compositions repeatedly focus on favoured motifs – a dining-room table, the view from a window or his lifelong partner Marthe De Méligny stretched out in a bath. They rely less on traditional modes of pictorial structure than a voluptuous use of colour that comes not from nature but his own interior logic.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

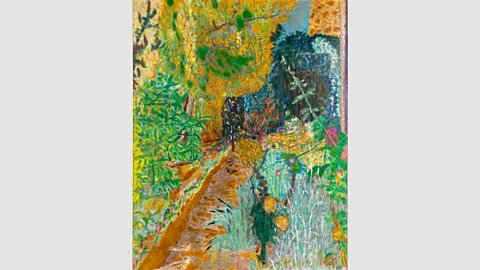

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USAVibrant shades of viridian green miraculously exist in harmony with the bright blues and oranges of a landscape, while elsewhere shades of mauve, gold and blue ripple across the walls of a bathroom. The resulting compositions combine psychological insight with an often sublime poetic sensibility.

More like this:

The deceptive joyfulness of his works combined with the difficulty of identifying him with any one artistic movement has sometimes led to the ground-breaking nature of his work being overlooked. A new exhibition at London’s Tate Modern hopes to show that his continuous and radical experiments with colour and form, which sometimes took him to the brink of abstraction, in fact make him one of the most innovative and unique painters of the 19th and 20th Centuries.

Tate

TateLike many Western artists who came of age in the late 19th Century, the bold use of colour and previously unseen use of perspective in Japanese ukiyo-e prints were to prove eye-opening to Bonnard. As would the colourful, intensely decorated crêpe papers, also from Japan, that he found in department stores and with which he covered the walls of his room.

Like his colleagues in Les Nabis, the artistic movement he was loosely d with throughout the 1880s and ‘90s, Bonnard was also heavily influenced by Gauguin’s work and his ability seemingly to allow lines and colours to speak for themselves.

Alamy

Alamy“I realised that colour could express everything with no need for relief or texture. I understood that it was possible to translate light, forms and character by colour alone,” he later wrote.

Bonnard developed a highly decorative style that abandoned three-dimensional modelling in favour of flat planes of colour. The aesthetic can be clearly seen in The Croquet Game (1892) in which the composition abandons all pretence of conventional perspective.

However, as the century drew to a close and the of Les Nabis began to go their separate ways, Bonnard increasingly turned his focus onto dark, bourgeois interiors and hazy, sensual portraits of Marthe in the half-light of her bedroom. “There is a period around the turn of the century where his work is fairly drained of colour,” says Tate Modern’s Head of Displays Matthew Gale.

Indivision A/A Ostier

Indivision A/A OstierA turning point seems to have been a visit to the South of in 1909 which struck him as being “like something out of The Arabian Nights”. He wrote enthusiastically to his mother about “the sea, the yellow walls, the reflections as full of colour as the light”. At the same time he was turning to a new way of working which involved relying heavily on the accumulated memory of subjects dear to him, be it Marthe, a favoured view or a piece of crockery, aided by assiduous sketching and note-taking.

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Minneapolis Institute of ArtBonnard’s uniquely personal response to his subjects was given a new chromatic intensity as muted colours gave way to radiant orange-reds and a myriad of purple and mauve hues. “I think he finds that if he pushes at colour combinations, it can express his personality more directly than he had found up to that point,” says Gale.

In the moment

A landmark in his development was Dining Room in the Country (1913), in which a red-clad figure gazes languidly from the bright heat of the day into a shady room whose icy blue tablecloth hints at cool respite, despite the rich orange tones of the walls. “The quality of light outside that he captures is on a completely different to the temperature inside, and that’s an amazing achievement,” says Gale.

Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ Roger-Viollet

Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ Roger-ViolletThe painting is all the more remarkable for the way in which it breaks down traditional hierarchies of painting, merging landscape, still-life and the figure “all in one sort of mash up… which brings into focus the sense of living now in this place in this moment,” says Gale.

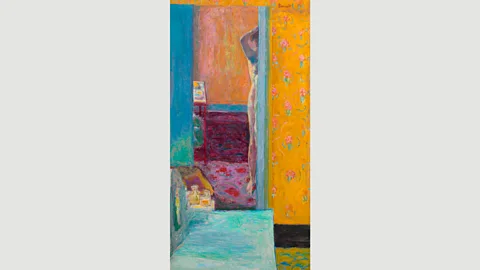

The curator is equally struck by The Open Window, Yellow Wall (1919), whose innovative form and colour combinations veer towards the abstract. “Two-thirds of the painting is basically a yellow wall, and there’s a view out through the window and a huge slab of blue underneath that. If you took out the details of the houses beyond you’d be looking at a Diebenkorn,” he says. “To be able to maintain a balance between dense blues and a huge amount of yellow – he brings in accents of purple to make that work – is just extraordinary.”

Ville de Nice Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret/ Photo Muriel ANSSENS

Ville de Nice Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret/ Photo Muriel ANSSENSAlthough the overwhelming brightness of much of Bonnard’s oeuvre seems to make him a painter of happiness, Gale is intrigued by “the paradoxical relationships between colour and melancholy”. He says: “It’s almost as if he’s trying to capture the mood as it es into the past – trying to fix it before it gets out of reach. It’s sort of Proustian.”

Colour of love

This is perhaps most evident in the many paintings he composed of Marthe in the bath. His familiarity with the subject allows his vivid imagination to use light to transform the bathroom into a glittering, jewel-like chamber, but the awareness that her obsessive bathing rituals were a result of delicate health also imbues the works with a sense of poignancy.

His palette can also be used to express a sense of yearning in works such as Summer (1917), painted as World War One raged around him, in which bright-orange figures in a pastoral idyll appear within a faintly menacing landscape of lime greens and vibrant blues. Gale thinks that “here he’s looking forward to the return of peace after the devastation of war”.

Bonnard’s lengthy career saw him live through another war, the tragedy of the era heightened by the death of Marthe in 1942. Although his landscapes from this period are sometimes reduced to little more than strips of colour, he “hesitates before going that final step into abstraction. It’s not necessarily something that he either needs or wants to do,” says Gale. “He’s his own man, he’s made his own direction as it were.”

Fondation Marguerite and Aimé Maeght, Saint-Paul-

Fondation Marguerite and Aimé Maeght, Saint-Paul- That direction is seen in all its glorious fruition at the war’s end when he was able to finish his magnificent last large-scale composition, The Studio with Mimosa (1939-46). It’s “an extraordinary combination of orange and yellow and green and violet all sitting alongside each other in complete harmony,” says Gale. One can’t help but see it as a joyous celebration of life in the wake of all the horror that had gone before – and a triumphant finale to a uniquely creative career.

Private collection

Private collectionAlthough modest and introverted by nature, Bonnard appears to have been aware of the value of his artistic legacy and expressed the wish that his painting would “endure without craquelure”, in order that he could present himself to the artists of the future “with the wings of a butterfly”. Canvas wings, in miraculously harmonious shades of orange, yellow, green and violet whose beauty and melancholy remain undimmed.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.