Why don't we plan better for hurricanes?

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Mark Wilson/Getty ImagesWe know how to reduce the human and economic fallout, argues Amanda Ruggeri, so why isn’t more being done?

2 September 2019: This article from our archive originally appeared in September 2017, but we have republished it to provide context to the news of Hurricane Dorian - the most powerful storm to hit the Bahamas since records began.

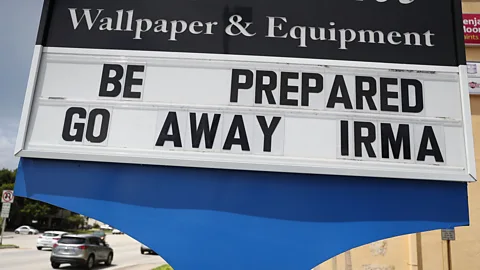

As I write this, Hurricane Irma has flattened the Caribbean islands, killed at least 10 people and is barrelling towards south Florida. My father and his partner, who live in an evacuation zone just north of Miami, have been weighing their options: the relative’s house inland where they had been planning to go is now in an evacuation zone, too. No one knows what the storm holds for the US, but with winds at 185mph (296km/h) and a trajectory headed straight for Florida, it is unlikely to be good.

All of this comes as the US still reels from Hurricane Harvey, which brought floods and destruction to Texas and into Louisiana. If that weren’t enough, two other hurricanes – Jose and Katia – have begun spinning swathes through the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

This year's hurricane season is producing tragic, terrifying crises. Their sheer scale and consequences make them seem like one-offs. Politicians and reporters alike are reaching for words like “unprecedented” to describe their effects. From an individual standpoint, that makes sense. For people like many of Houston’s residents, who have never seen anything quite like this before, an aberration is exactly what this feels like.

But natural disasters aren’t aberrations. They’re all-too-frequent occurrences – ones that, if anything, are becoming more damaging. And thinking about each one in isolation each time it happens has a dangerous, even deadly, effect: it discourages us from adequately preparing for them to begin with.

There are known, sometimes simple, ways to lessen the human and economic toll of disasters like these. The trouble is, doing so requires politicians, businesses and the public to change how we think about the future.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Mark Wilson/Getty ImagesIt’s human nature to put off preparing for something that seems relatively unlikely to happen. That’s particularly true when those preparations cost money. (Would you rather budget to pay for the roof over your head that you need tonight, or to pay into a life insurance policy that your family might not need for years?) But as anyone knows who has gambled by not paying for health insurance, and then fallen ill, paying out for that preparation now could save far, far more in the future.

There is, of course, the irreplaceable human cost. But there’s an economic cost, too. As BBC Future has explored before, in the US, for example, one study showed that for every $1 the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema) paid for disaster preparedness, it saved $4 in costs later. While the exact amount saved (and in some cases, if money is saved at all) varies, one recent survey of disaster mitigation efforts around the world – from raising floors in flood-prone homes in Samoa to installing volcano monitoring in the Philippines – found that, indeed, “disaster mitigation is cost effective”.

Organisations much bigger than a single person or a family, whether a housing authority or federal government, are meant to have the kind of birds-eye view (and disionate, numbers-based analysis) to know and act accordingly. They sometimes do. In Florida, for example, where the devastation of Hurricane Andrew in 1992 brought home the importance of planning (and often paying) ahead, a raft of policy changes meant that most houses now include hurricane-resistant glass, roofs and concrete-pillar reinforcements (although even these building codes may need adjustment in the face of sea level rise).

“When you think back to Hurricane Andrew, we ed some very aggressive wind codes here,” Nichole Hefty, the chief sustainability officer for Miami-Dade county, told me when I was reporting last March from south Florida. “There was some outcry from developers saying ‘No, it’s too costly, we can’t do this.' But we did it, and it was important. Now our community is much more protected than another communities, and it’s considered one of the strongest building codes, in of protection, in the country.”

Marc Serota/Getty Images

Marc Serota/Getty ImagesBut with their budgets squeezed by must-fund-now priorities like schools and police; with developers resisting regulations; and with many politicians only looking into the future for the length of their term, many policy-makers also often roll the dice – or are simply too overwhelmed to make disaster mitigation a priority.

Houston has been one recent, and tragic, example. Part of the reason the flooding was so devastating is the city’s flat, low-lying and poorly-draining geography. But other reasons were manmade, like the recent construction boom along with outdated flood protections, building regulations and drainage systems. Politicians were warned, but did not act on advice.

This put-it-off-until-later mentality influences more than government policy. The reticence of individuals, communities and even corporations to financially protect themselves from natural disasters is another example. Last year, just 26% of economic losses from natural disasters worldwide were covered by insurance. And those losses weren’t pocket change. Disasters in the US alone cost $210bn (£161bn) – the costliest year since 2012. The priciest peril? Flooding, for the fourth year in a row.

One common insurer for flood-prone communities is Fema’s National Flood Insurance Programme (NFIP). But, ironically, even that programme has not prepared fully for the extent of the crises the US has faced: although NFIP runs nearly $25bn (£19bn) in debt, it wasn’t until last September that, for the first time, it bought its own reinsurance programme – essentially, an insurance policy to protect against its own potential losses. Renewed in January 2017, and given that losses from Hurricane Harvey alone are calculated to estimate between $10 and $20bn (£7.6 to £15.2bn) total, triggering the policy’s payout, the reinsurance programme already seems to have been worth it. But in some ways, NFIP is late to the game. Even the buffer that reinsurance provides will only help keep NFIP from accruing more debt on future disasters – not help pay off the debt that’s already there, much of which will probably still go to the taxpayer.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Joe Raedle/Getty ImagesIn many ways, we’re all treating these kinds of disasters, including hurricanes, as one-offs. But as the violence of this hurricane season alone has shown, they aren’t. And neither are the kind of roof-ripping, life-destroying storms that we’re seeing now. In fact, hurricanes are becoming more powerful. As Nasa has reported, studies have shown that compared to 20-25 years ago, hurricanes are becoming stronger more quickly, hurricane wind speeds are 5% higher and that they include more water vapour (read: heavier rain).

That’s all at the same time, of course, that both populations and property values have increased along hurricane-prone coastlines – helping to make extremely expensive natural disasters more frequent. In the US alone, 2016 saw 15 billion-dollar events; in 1980, there were the equivalent of three (adjusting for inflation).

Even places that haven’t been historically hurricane-prone are not immune. At first glance, for example, it makes sense that Houston hasn’t nailed the details when it comes to flooding preparedness: there is a 1-in-500 annual chance of a hurricane like Harvey hitting Houston.

It’s seen three of those 1-in-500 storms in the last 10 years alone.

Of course, cities like Houston, and even Miami, may not see other hurricanes like Harvey and Irma for another 10, 50, even 250 years. They could spend money and time ing new regulations and zoning codes. They could funnel money away from other priorities and toward new drainage systems, higher seawalls, stronger levees. NFIP could spend billions on expanding its reinsurance programme. And for years, citizens could grumble about what a waste it all was.

That’s the problem with historic data and averages. None of it is a crystal ball.

But with the toll of natural disasters mounting, even communities with little historic experience of them might want to ask if that’s a gamble they want to take.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.