The Nasa mission that broadcast to a billion people

Nasa

NasaThe Apollo programme was on a knife-edge when Apollo 8 blasted off 50 years ago. Its success paved the way for the Moon landings months later – and it captured the imagination with a Christmas message from orbit.

It is 21 December 1968, 7.50am, Cape Kennedy, Florida. The Apollo 8 crew – Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders – are strapped into their couches, some 110 metres (363ft) above the ground at the top of the first manned Saturn 5 rocket – the most powerful machine ever built. As the final seconds tick down to launch there is little to say and little more they can do. Some four million litres of fuel is about to ignite beneath them. They are, as the watching BBC TV commentator helpfully put it, “sitting on the equivalent of a huge bomb”.

There is every reason to be concerned. During the previous unmanned test of the Saturn 5, a few months earlier, severe vibrations and g-forces shortly after launch would have likely killed anyone on board. Although the rocket has since been modified, Borman’s wife has been discretely warned by Nasa that her husband has about a 50/50 chance of surviving the mission.

The performance of the Saturn 5 rocket isn’t the only thing worrying Nasa management. Apollo 8 is a mission of firsts – a giant leap forwards in the race to land a man on the Moon. It will be the first manned spacecraft to leave Earth orbit, the first to orbit the Moon and the first to return to Earth at a staggering 40,000km/h (25,000mph). The mission is a calculated gamble by the space agency to beat the Soviet Union to our closest neighbour.

You may also like:

“It was a very, very bold decision,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, Apollo Curator at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. “Everyone within the agency knew it was an extraordinarily risky mission and there was a lot of criticism, most famously by British astronomer Sir Bernard Lovell, of the United States putting human life at risk.”

In fact, Apollo 8 was never intended to be so ambitious. It was originally planned as the first test of the Apollo lander in Earth orbit, but production of the lander was running late. On top of that, the CIA warned that intelligence suggested the Soviets were about to attempt their own manned flight around the Moon (you can read how close they really were here.)

Nasa

Nasa“Everyone forgets that the Apollo programme wasn’t a voyage of exploration or scientific discovery, it was a battle in the Cold War,” Borman says, “and we were Cold War warriors.”

Despite the qualms of his bosses, and after only four months of intensive training, Borman, a former military fighter pilot, says he was never in any doubt the mission would succeed.

“We were obliged to change the mission to accomplish the Moon landing before the end of the decade, that President Kennedy had promised,” Borman says. “In my opinion the mission was extremely important not just to the US but to free people everywhere.”

With the engines lit and countdown at zero, the Saturn 5 slowly lifts from the pad and accelerates into the clear blue Florida sky. “I felt like we were on the point of a needle,” says Borman. “The noise gave the impression of enormous power – I had a feeling of being along for the ride, rather than being in control of anything.”

“It gets very hard to breathe, almost impossible to move and your eyes flatten out so you get tunnel vision,” he recalls, “it’s an unusual feeling.”

Some eight minutes later they are in orbit. After one and a half orbits, they fire-up the rocket’s third stage engine and blast away from the Earth towards the Moon. Then, two days and 402,000 kilometres (250,000 miles) later, at 8.55 GMT on Christmas Eve, Borman performs the crucial engine burn on the Apollo service module that will put the spacecraft into orbit around the Moon.

“I think we fired the engine something like four minutes to slow down enough to get into lunar orbit,” Borman recalls. “I’m about three quarters of the way through that and we looked down and there was the Moon.”

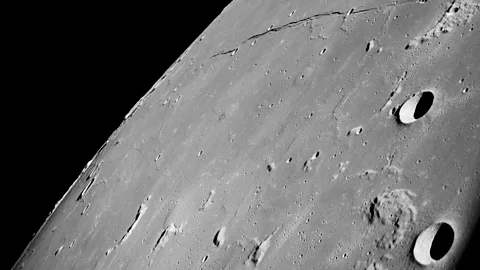

The crew were the first humans to ever see the far side of the Moon with their own eyes. “I don’t think anything I’d studied prepared me for the really troubled nature of the lunar surface – it was messed up beyond belief,” says Borman. “It was terribly distressed with holes, craters, volcanic residue, so it was a very interesting first view of a different world.”

Nasa

NasaAnd it isn’t only the view of the Moon that catches them by surprise. Some 75 hours and 48 minutes into the mission, Anders spots the blue marble of the Earth rising above the lunar horizon and scrambles for colour film to capture the moment.

“The contrast between the distressed Moon and beautiful blue Earth was remarkable, the Earth was the only thing in the entire Universe that had any colour,” says Borman. “You could see the white clouds, the brownish pink continents…we’re very fortunate to live on this planet.”

A mission that had been conceived as a risky test of human technological ingenuity and astronaut bravery is being transformed into an unexpectedly emotional experience for those involved. The Earthrise image wouldn’t be published until Apollo 8 returned to Earth but for Christmas 1968 the crew have another gift for the planet.

“Before the flight, the Nasa public affairs officer told Borman that they expected about a billion people – a quarter of the world’s population – to be tuning into their Christmas Eve TV broadcast from lunar orbit,” says Muir-Harmony. “More humans would be hearing their broadcast than any other human voice in history and he was just told to say something appropriate.”

“That is one of the most remarkable moments of a free country,” says Borman. “Can you imagine if the Soviets had been up, we’d be talking about Lenin and Stalin and we’re just told to do something appropriate.”

But coming-up with “something appropriate” proved far from easy. “The three of us and our wives tried to figure it out,” Borman says. “We couldn’t.”

He turned to a friend of his, who in-turn asked veteran war correspondent Joe Layton. “As I understand it, he was sitting up all night throwing crumpled-up paper away when his wife walked by, and his wife was a former French resistance fighter, she suggested why don’t you start at the beginning?”

Nasa

NasaWith the TV cameras rolling, and as the spacecraft approached lunar sunrise on Christmas Eve (US time), the crew start to read from the Book of Genesis. “In the beginning…” begins Anders. Borman concluded the broadcast with “good night, good luck, a merry Christmas and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

“We were quite convinced it was the most appropriate thing to do because there is a sense of awe on my part, at least, that the Universe is bigger than all of us,” says Borman. “It’s too orderly and it’s too enormous not to have some sort of divine creation.”

But the mission is far from over. On Christmas Day Borman fires the engine again to leave lunar orbit. “The Earth orbit insertion burn was accomplished on the far side of the Moon, out of touch of the ground – had it failed, I’d still be circling the Moon.”

“Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus!” exclaims Lovell as they re-establish with the ground. And Santa even delivered. Covered in specially designed fire-proof festive ribbon, the crew unwrap their present from mission control: a turkey dinner with gravy.

“[Our boss] Deke Slayton had also smuggled three shots of brandy on board but we didn’t drink that,” Borman says. “I didn’t want it to be blamed for anything going wrong, so we brought it home.”

“I don’t know what happened to mine,” he adds. “It’s probably worth a lot of money now.”

On 27 December, the crew return to Earth – splashing-down so close to their target in the Pacific Ocean that the recovery ship had to move out of the way. It was the perfect end to a perfect mission, the final proof that the gamble of flying to the Moon will pay off.

“Apollo 8 was not only a great scientific and engineering accomplishment,” says Muir-Harmony, “it broadened the bounds of human experience, it affected the way we appreciated the Earth and our place in the Universe.”

For Colonel Borman, at 90 still a formidable Cold War warrior, the great achievement of his final mission was to get America a step closer to the Moon.

“I’ll be honest with you, I don’t really think about the legacy of Apollo 8,” he tells me. “Frankly after Apollo 11 was successful [in landing men on the Moon], I had no more interest in the programme. I ed to help fight a battle in the Cold War and we’d won.”

To hear more from Frank Borman, Apollo 8 and astronauts talking about Genesis and their own religious experiences, listen to Richard’s Radio 3 programme broadcast on 22 December: Message from the Moon

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.