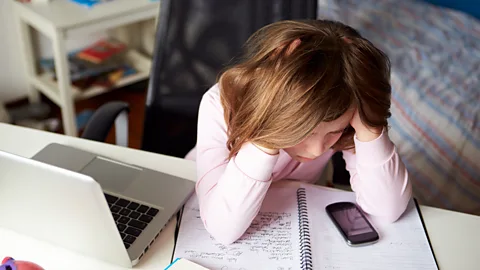

Why is ADHD missed in girls?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany more boys get diagnosed with ADHD than girls. But more girls may have the condition than we think – and their struggle to receive a diagnosis can affect their whole lives.

Emily Johnson-Ferguson’s mind has been racing for as long as she can . The eating disorders she began suffering from as a teenager were her attempt to slow down her brain. Doctors tried to blame them on family problems and stress, but she knew that wasn’t it.

It was only last year, aged 42, that she finally got to the root of her problems: ADHD.

Johnson-Ferguson is not alone. Though the stereotypical image of ADHD is a boy bouncing around a classroom, that’s not the whole picture. Girls can have ADHD, too – and many go without diagnosis, and without treatment that could change their lives.

You might also like these other stories in the Health Gap:

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that comes in three types: inattentive, hyperactive/impulsive, or a combination of both. People with inattention may forget things, struggle to get organised, and find themselves easily distracted. Those with hyperactivity and impulsivity might struggle to stay sitting down, constantly fidget, and interrupt conversations.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe condition is usually first diagnosed in childhood, but most people don’t grow out of it. For those whose symptoms are missed as children, living with undiagnosed ADHD as they move into adulthood causes problems.

“When I was left to my own devices at university I just couldn't concentrate at all,” says Johnson-Ferguson. She switched courses, but it didn’t help. Her bulimia persisted throughout university, and for the next 20 years she also used alcohol, caffeine, and sugary drinks to self-medicate – common among adults with ADHD.

As her marriage broke down, she started to find life even more difficult. In an effort to start afresh, Johnson-Ferguson gave up her bad habits, but found no respite from her symptoms; instead, they got worse. At her lowest point she was spending days on end in bed. “At that time I couldn’t focus on anything,” she says.

Attention deficit

There is a concrete difference between the prevalence of ADHD in boys versus girls. In one study of 2,332 twins and siblings, Anne Arnett, a clinical child psychologist at the University of Washington, found that a sex difference in diagnosis could be explained by differences in symptom severity: boys tended to have more extreme symptoms, and a broader distribution of symptoms, than girls.

“It's an actual neurobiological difference that we're seeing,” says Arnett. It’s not clear why that’s the case, but it could be that girls have a protective effect at the genetic level, she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut the true size of the difference is unclear.

When it comes to real-world diagnoses, boys far outweigh girls. In studies that look at who meets ADHD criteria in the population as a whole, however, the ratio still favours boys, but less so. Depending on which research you look at, the ratio of boys to girls with ADHD could be anywhere between 2:1 and 10:1.

“It would seem to suggest that there's actually a lot more females who are affected by ADHD,” says Florence Mowlem, an associate at healthcare consultancy Aquarius Population Health. “Yet, for some reason that we don’t quite understand, they don't seem to be getting the clinical diagnosis as often as males.”

Research suggests that girls need to have more severe, and more visible, symptoms than boys before their ADHD will be recognised. In one study of 283 children aged between 7 and 12 years old, Mowlem and colleagues looked at what differentiated both boys and girls who met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD from those who had a lot of ADHD symptoms, but not enough to be diagnosed.

Mowlem, who was PhD candidate at King’s College London at the time, found that parents, in their own ratings, seemed to play down girls’ hyperactive and impulsive symptoms, while playing up those of boys. They also found that girls who did meet the criteria tended to have more emotional or behavioural problems than girls who didn’t. This was not the case for boys.

In a similar study of 19,804 Swedish twins published last year, Mowlem and her colleagues found that girls, but not boys, were more likely to be diagnosed if they suffered from hyperactivity, impulsivity, and behavioural problems.

Girls could also be better at compensating for their ADHD symptoms than boys, similar to how girls with autism mask their symptoms.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Girls are far less likely to bounce around the classroom, fighting with the teachers and their colleagues,” says Helen Read, a consultant psychiatrist and ADHD lead for a large London NHS Trust. “A girl who did that would be so criticised by peers and other people that it is just far harder for girls to behave in that way.”

Even when they are hyperactive, girls are more likely to be over-talkative, or rebellious – a bit of a wild child, she says. That might not be recognised by parents or teachers as being caused by ADHD, especially as we expect girls to be more sociable than boys anyway.

But more research is needed before we’ll know how big a problem this is.

Symptom similarity

If girls are losing out because they have less stereotypical symptoms, they might not be the only ones: boys with purely inattentive ADHD are probably being missed, too.

It’s a commonly held belief that girls are more likely to be inattentive than boys. But that’s a myth, says Elizabeth Owens, assistant clinical professor in the department of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. She says the current best evidence shows that rates of inattention are the same for boys and girls.

“The inattentive presentation is actually more common [among both boys and girls], but it tends to be under-recognised or under-diagnosed, because the kids aren't typically causing problems in the classroom,” she adds.

In fact, girls and boys with ADHD are much more similar than they are different, says Owens. “It underscores the fact that ADHD and girls is serious. For a long, long time, it was discounted, or overlooked.”

Alamy

AlamyOne difference, though, is that girls with combined ADHD – who have both inattentive and hyperactive symptoms – are at higher risk of self-destructive actions as they enter adulthood. Girls with ADHD are also more likely to develop anxiety and depression later in life.

As part of a study that started in the 90s, Owens and her colleagues followed 228 girls, 140 of whom had ADHD, over two decades. At the second and third follow ups, when participants were on average aged 19 and 25 respectively, they found that girls who’d been diagnosed with combined ADHD in childhood were at higher risk of self-harm and attempting suicide.

In theory, recognising and treating ADHD early should help to mitigate this risk – although Owens says that, as yet, there’s no evidence to show this works. “ADHD is a chronic condition,” she says. “It's not something you can treat and it'll go away.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTreatment for ADHD can, however, make a huge difference day-to-day.

Shortly after Johnson-Ferguson was finally diagnosed, she started taking medication, a stimulant commonly used to treat ADHD called lisdexamfetamine. “The next day I just sat down and watched a whole EastEnders,” she says. “It was like walking in slow motion for three days.”

She has to work hard to ensure she reaps the benefits of the drugs – exercising, eating healthily, drinking less, and forgoing caffeine – but the changes have been worth it. “The planning that I can do at work now is incredible, it’s like I’m a different person,” she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBeyond medication, knowing that the problems you’ve been facing throughout your life are not your fault can also be a huge weight lifted. Johnson-Ferguson describes her life pre-diagnosis as “42 years of feeling completely different to everybody on the planet”.

Now, she’s able to channel the positive aspects of her ADHD – hyper-focusing on short term projects – into a successful career in theatre marketing, while better understanding her shortfalls.

But many are not so lucky. Until we let go of the stereotypical image of what ADHD looks like and get to the bottom of why girls with the condition are being missed, plenty of women will end up living with symptoms that have drastic effects on their lives, without knowing they could get help.

This story is part of the Health Gap, a special series about how men and women experience the medical system – and their own health – in starkly different ways. Do you have an experience to share? Or are you just interested in sharing information about women's health and wellbeing? our Facebook group Future Woman and be a part of the conversation about the day-to-day issues that affect women’s lives.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, Travel and Music, delivered to your inbox every Friday.