The problem of thinning Arctic sea ice

Sebastian Grote/AWI

Sebastian Grote/AWIThe great freeze that covers the Arctic Ocean with sea ice missed vital months of cold conditions this year, presenting a surprising challenge to the largest Arctic expedition in history, but one unusual ice floe offers them some hope.

At the crack of dawn, the leaders of the expedition line up with binoculars on the bridge of the icebreaker Polarstern. The day is overcast and the light is flat. Our ship is floating in front of a patchwork of dark new ice and white snow that looks much like any other. It takes me a minute to realise that there is a much larger floe in the distance.

“We have just parked this far away so as not to damage it,” says Stefan Hendricks of the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), an ice expert on the Mosaic expedition, the largest-ever scientific voyage to the Central Arctic. Just in front of the bow of the ship is a refrozen lead – a large fracture in the sea ice – covered in a thin layer of blackish-grey ice. Beyond the lead is the white expanse of the floe. (Read more about the Mosaic mission to the Arctic.)

Matt Shupe of the University of Colorado, who had the initial idea for the expedition, and Markus Rex of AWI, who is now leading it, lean over a pair of images on a screen. They try to orient themselves and match up the information from the ship’s radar to what they can see out of the window. They are looking at a large ice floe, about 2.5km (1.5 miles) by 3.5km (2.2 miles), in an elongated hexagonal shape. They are assessing its potential as a home for the expedition over the next year.

As one of the few journalists ing Mosaic’s scientists on their voyage to the Arctic, it will be somewhere I too may be spending time over the next few weeks before I begin the long journey home. It is a tense moment, as much of the expedition will hinge on this choice.

Rex seems convinced that the floe in front of us is indeed the one in the satellite picture. “I think we have the right piece of ice,” he says.

You might also like:

The first mate guides the ship over towards it in a curved line. With other floes we’ve encountered we have clipped a piece off the edge with the ship to see how thick it is. As we move closer I ask if we will do the same with this one. “No, no,” says Hendricks.

There is a new, much more cautious attitude to this piece of ice. “We don’t have many floes,” says Allison Fong, leader of Mosaic’s ecology team. “We shouldn’t be destroying any, let’s put it that way.”

Esther Horvath/AWI

Esther Horvath/AWIAs we near the floe, we have to cut through a neighbouring piece of ice instead. Large fragments bob vertically next to the hull to reveal a cross-section. A red and white two-metre (6.6ft) measuring stick, painted at 50cm (20in) intervals, points out from a lower deck to aid the team on the bridge in judging how thick it is. Recently, the solid layer of blue ice in between snow on top and mushy rotten ice below, has rarely made it past the first gradation on the measuring stick.

The team peers down out of the starboard windows. “That’s thick. That’s one point… that’s over one [metre],” says Fong. If the neighbouring floe we have been eyeing up is the same, it could be promising. “Even the new frozen bits, they are also thick enough.”

The new layer at the top is the firm ice that can weight. The older rotten ice below is unreliable, although there is a question about whether a thicker layer of it helps or hinders refreezing during winter.

“Look at this chunk,” says Fong, pointing out another large piece of ice more than a metre (3.3ft) thick that has eased upwards at the starboard side.

Sebastian Grote/AWI

Sebastian Grote/AWIUp close, however, the floe itself doesn’t look particularly imposing. Its surface is level with the water that is freezing at its edges. There is no platform above the water to offer some protection and refuge. Instead, the floe merges seamlessly with the sea around it, rising in the distance to what could be a more rugged area towards the centre.

“The thing is, I’m not sure this piece of ice is even safe to walk on,” says Rex.

“We’re too far away to tell,” says Fong.

“In that ridged area there are holes and gaps,” says Rex, gesturing towards the central region. “It would be good to have those survival suits. Take the floats also.”

“If you really think it’s not safe to walk on then I don’t really know what you want to do there,” says Verena Mohaupt, logistics lead for the expedition. One of her responsibilities is equipping people to deal safely with the hazards of the ice.

But the idea of wearing survival suits – which are waterproof and aid flotation in case you fall into the water – appears to give the team a little confidence. “If you guys go in survival suits, we don’t need to worry,” says Fong.

A small surveying party including Shupe and Hendricks is to explore the floe. Mohaupt gives them ice picks, ropes, two radios and an emergency backpack. They will also be accompanied by a trained bear guard. Polar bears are the other main danger on the ice, besides falling into the sub-zero waters. The guards that accompany every group that ventures onto the ice have several methods of defence, starting with flares to scare them away, and ending with a rifle as a last resort.

But each member of the party has been trained to handle the rifle should anything happen to the guard.

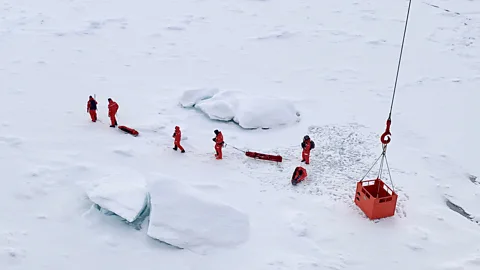

It is -6C (21F) , with the chill factor from the northerly winds making it feel more like -22C (-7F). The surveying party clambers into an open-topped red metal box called a mummy chair, which looks like the basket of a hot air balloon, to be winched by a crane over the side of the ship and down onto the ice.

Martha Henriques

Martha HenriquesClimate change has been thinning the Arctic sea ice for decades. But no-one on the expedition quite appreciated just how fragile it had become until they got here. (Read about how thin ice has hampered the expedition.)

“From the air it looks so beautiful,” says Jari Haapala of the Finnish Meteorological Institute. Haapala was on the first helicopter flight from the Russian vessel the Akademik Fedorov, which has accompanied Polarstern on this first leg of its journey. The flights to explore nearby floes have been going on in parallel with the efforts on board Polarstern. But the view from the air was deceptive. Survey teams have been drilling into the ice to measure its thickness and quality.

“It was amazing to see the drills went so quickly through,” says Happala. "Usually the ice is quite strong – it takes time to drill. It was a big surprise that these floes were so large but they hadn’t disintegrated yet.”

This is not welcome news for Mosaic. The expedition needs a particularly stable floe because of the scale of the research camp they plan to build on it. The scientists want to spend the next year there, measuring the atmosphere, ice, ocean, biogeochemistry and ecosystems in the Arctic throughout – an ambitious plan that has never been done on this scale. The data they obtain will help to answer a raft of questions about how climate change is transforming the Arctic environment, and what that will mean for the rest of the world in the coming decades.

Until now, the major challenge has been finding a “sweet spot” from which they can allow themselves to become frozen into the sea ice and begin drifting. They have to avoid ing into known danger zones, areas inaccessible to resupply operations, and the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone, where they are not permitted to do research. If the ship drifts into this area, the instruments would have to be switched off and data-gathering halted. But as time as gone on, another challenge has emerged – finding a piece of ice in this sweet spot capable of ing them.

The camp was planned to include heavy instrumentation and a runway, ploughed flat by large pistenbullies, similar to the snow groomers seen at ski resorts around the world. But this is looking less and less realistic. Many of the best floes identified as being at least 80cm (32 inches) thick in satellite images have turned out to be less than half that.

“Put that ship alongside such a floe and the first storm will press this ship right through it sideways,” says Rex. “It will just sail through the floe.”

Sebastian Grote/AWI

Sebastian Grote/AWIThe ice is deceptive when it comes to judging distance. Without the visual cues of ordinary life for reference – buildings, roads, trees – it is hard to tell if the shadowy grey-white ridges are hundreds of metres or kilometres away. We watch from the deck as the ice-survey party become specks as they trek into the distance. Occasionally they pause to take measurements – drilling holes into which they lower a measuring stick, and pinging electromagnetic pulses from a device they pull along in a sledge. The pulses are reflected by the boundaries between snow and ice, and where ice meets water, giving an indication of their thickness.

The team are gone for several hours, dark dots traipsing in lines up and down the floe, pausing, moving off again through drifts of snow and over ridges. Slowly, the results trickle in to the bridge by radio. We hear of depths first of 60cm (two feet), and then of more than 1m (3.3ft). By the end of the day a detailed picture of the floe is forming and it is clear this is not like the other bits of ice we have encountered.

But Rex is still cautious. “We budgeted to look at 20 floes,” he says. “This is our second. I would be surprised if our second floe is the one. There is expectation in this period and people get nervous. That’s not what we want.”

Despite Rex’s assertion that we are ahead of schedule, there is an urgency to reach a decision. The height of the sun rising above the horizon is getting lower with every day and soon it will not appear at all, making practical work on the ice a lot more difficult.

“We need to make a decision about this floe as soon as we can,” says Matt Shupe, when he returns from the floe. “It’s got its qualities that might be good or bad. But if we are just sampling many other floes, then we’re going to have to bust them out quicker. We’ve already spent some time with this guy.”

AWI/Sebastian Grote

AWI/Sebastian GroteAfter one more day on the ice, it becomes clear this floe has a strong central section, with ice depths of up to 5m (16ft) – a thickness so far unmatched by anything the two ships have found so far. It appears to have been created from several floes merging under high pressure. Shupe dubs this rugged area the “fortress”. It appears as a luminous, bright patch in the otherwise dark grey satellite pictures the team are using.

“In that big part, the white part, it’s a war zone,” says Shupe. “I was standing in the middle of it, like, ‘how would we get a snow machine through this?’ Somehow we found ways. But there were areas that would drop off like 3m (10ft) – obviously you didn’t want to go there.”

Beyond the fortress, there are two large flatter zones. The larger of these two appears to be made of ice more or less typical of the region. It would allow the expedition to study what is happening to the ordinary, fast-disappearing young Arctic sea ice.

“Although it’s very inhomogeneous, very rugged, it’s still a solid piece of ice which can be used to moor the ship,” says Rex. “Therefore, I think this in itself could be a good argument for using this piece of ice. Then we can do a lot of science in the other part here, which is characterised mostly by melt ponds and some ridged structures.”

Preliminary analysis suggests that the ice in this region is much younger than usually seen at this time of year. The ice around the ship started forming about 300 days ago – around two months later than the usual onset of the Arctic winter freeze. Those two months of missing freezing make a big difference, reducing the ice thickness by around half.

TerraSAR-X/DLR 2019

TerraSAR-X/DLR 2019After two back-breaking days of work on the ice by Shupe, who is now fighting off a cold, and the rest of the survey team, Rex’s first close look at the floe is by helicopter. The floe, clearly very dynamic, has already changed.

A large crack runs through the ice from west to east, almost severing about a fifth of the floe beyond the northern edge of the fortress. There is a storm due to through in the coming week and the floe is in a shear zone, with currents pulling it in different directions. This section of the floe is not expected to last long. “This is just very thin ice, very flat, recently formed,” says Rex. "I think we are going to lose this one.”

But the rest of the floe, particularly the fortress, still looks solid. To make the final decision, the leadership on both ships meet on Polarstern.

“The standard floe this year, due to the warm summer and the overall ice conditions, is not really suited to moor a ship to it and set up a big research camp,” says Rex. “So, the task we are facing right now, the thing we have to solve, is not to look for the perfect floe for our expedition but to select the best one we can find.”

The results of the surveys carried out from the Fedorov reveal more of the same kind of floes that have been found all over the Arctic this year. From the North Pole to the Chukchi Sea, Russian long-range Mil Mi-8 helicopters have found a consistent picture throughout a large swathe of the Central Arctic. Large floes are few and far between. Those that do exist are universally thin and riddled with melt ponds.

After the formalities, the discussion is fairly brief. It is clear that there is only one viable option.

AWI/Markus Rex

AWI/Markus RexA few days later, Polarstern moors to the fortress floe, at 85 degrees north and 137 degrees east. Not, as originally planned, by lining the ship up carefully to one edge so as not to damage the fragile outer ice – but instead by ramming noisily 500m (1,640 feet) towards the fortress. The captain wants to be securely embedded to get the best mooring.

“He took the ship in pretty quick,” says Shupe. “Fortunately there was not much damage to the surrounding ice.”

Over the coming days the team will begin constructing their ice camp around Polarstern, carefully putting out equipment that the ice can until it grows thicker over the winter. The Akademik Fedorov, meanwhile, will set up a series of far-flung outposts stretching out tens of kilometres around, releasing scores of buoys and remote sensing stations that will give the bigger picture of the Arctic environment beyond the central floe. If the central camp is the fortress, then these will be the border posts of the Mosaic research camp.

AWI/Esther Horvath

AWI/Esther HorvathTo see this broader encampment established, I transfer over onto the Russian ship via its own mummy chair – this one looks like a giant bird cage festooned with faded ropes and plastic buoys. Alone in the cage with my bags, suspended between ships over the shards of floating ice, I notice that the mummy chair has a disconcerting bounce. Beneath this motionless, freezing skin lies 4,000m (13,120ft) of perishingly cold Arctic Ocean. The warm worlds inside the two ships seem fragile and small by comparison.

Fortunately it takes less than a minute before I am on the bow of the Akademik Fedorov. With the help of half a dozen people, I bundle up my kit and escape into the ship that is to be my new home.

But I can’t shake the feeling I had during the transfer. Soon I will step off the Fedorov and onto that thin crust of ice, very far from any kind of solid ground.

* Martha Henriques is a senior journalist at BBC Future. She is spending six weeks on board Polarstern and Akademik Fedorov as they embark on their mission. You can follow her progress on Twitter @Martha_Rosamund.

Frozen North

This article is part of our Frozen North series. Climate change is already transforming the Arctic. In many areas, what was ice is now open water. But in the most inaccessible reaches of the far north, how much has changed? And what will the knock-on effects be for the global climate?

The world’s largest polar expedition has just set off to answer those questions – and BBC Future’s Martha Henriques is one of the lucky handful of journalists onboard. In our series Frozen North, she reports from the Arctic’s floating sea ice as scientists seek to find out how this shifting environment will affect all of us.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.