The Mayan languages spreading across the US

Getty Images

Getty ImagesImmigrants from Mexico and Central America are taking their ancient languages to new territories.

Three days had ed since Aroldo's father died. Aroldo was still mourning, and he couldn't even bring himself to tend the cornfields his father had left him in their community in San Juan Atitán, Guatemala. At dinner, as he stared into the flames of the wood stove, feeling the weight of loss on his chest, he told himself it was time to breathe fresher air. Turning to his mother, who was quietly eating beside him, he said in Mam, the Mayan language spoken in their town: "Nan, waji chix tuj Kytanum Meẍ," – "Mum, I want to go to the white men's nation," meaning, the United States.

In Mam, his mother told him she would set things up, but first, he had to wait until the mourning period was over. A year later, with cousins in California willing to host him, Aroldo set out (the BBC has chosen not to name him in full to protect his identity). It took him more than four months to descend the slopes of the Sierra Madre, cross the deserts of Mexico and Arizona and reach the San Francisco Bay Area.

"[My father's] death put life in front of me and made me realise it was time to face it by myself," says Aroldo, in Spanish, which he also speaks. Behind him, a photo of his father, wearing a traditional hat and hand-knitted magenta shirt under a black capixay of San Juan Atitán, guards him on a chilly December night in the Bay Area.

One of the few things Aroldo took with him was his language, Mam, whose roots reach far back into the Mayan civilisations that ruled over Central America thousands of years ago. Today, Mam and other Mayan languages are expanding their reach, as indigenous people from Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala are spreading them in the US through immigration. In fact, in recent years, Mayan languages, originally spoken across the Yucatán Peninsula, have grown so common in the US that two of them, K'iche' (or Quiche) and Mam, now rank among the top languages used in US immigration courts.

The rise of these indigenous languages in Latin American immigrant communities in the US is only beginning to be fully understood, experts say – and has important implications for the communities and their needs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe San Francisco metropolitan area is one of the top destinations for Latin American immigrants. One in four of the Bay Area's more than seven million residents are Latinos, most with roots in Mexico and Central America, according to calculations based on US Census Bureau data.* The US government counts them all as Hispanic upon entering the country, a term denoting people from Spanish-speaking countries, even though for some of these migrants – like Aroldo – Spanish is not their mother tongue, but what they use to talk to those outside of their home villages. Others don't even speak Spanish at all, and only speak their indigenous language, according to several Mayan immigrants and experts interviewed for this article.

"Many Mam speakers come to the US and have a different set of needs, experiences and histories than monolingual Spanish speakers and those not from indigenous cultures," says Tessa Scott, a linguist specialising in the Mam language at the University of California, Berkeley. "If you call everyone from Guatemala 'Hispanic', you might assume everyone in that group speaks Spanish fluently, and they don't."

In California, a new law ed in 2024 requires state agencies to collect more detailed data on Latin American immigrants' preferred languages, including indigenous languages such as K'iche' and Mam, in order to better understand and meet their needs.

Besides needing different interpreters, Mayans and other indigenous immigrants face unique challenges that mestizo or white Latin Americans don't, and that often go unnoticed when all are covered under the blanket term "Hispanic", Scott says.

"Indigenous Guatemalans, many from Mayan cultures like Mam, frequently face intense discrimination and violence by people in a different social category, and this is what often drives them to come to the US, where they may seek asylum," she says. Labelling all Latin Americans as Hispanic can hide these complex social, cultural and ethnic hierarchies, and prevent asylum seekers from receiving specialist services such as legal help and trauma , she adds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe growth of Mayan communities in the US has also given their ancient languages new platforms, adding to a long and rich history. Though the ruins and carved hieroglyphs of ancient Mayan cities may seem like relics of a long-lost civilisation, many Mayan communities survived the Spanish conquest of the 16th Century and preserved their culture and languages. In places like the Bay Area, you can now find Mayan languages on the radio, in local news outlets or even in classrooms.

"We are as involved with the world as any other society," says Genner Llanes-Ortiz, a Maya scholar at Bishop's University in Canada. "We continue to speak our languages and use them not just to write our history, but to write new ways to deal with what affects us."

Mayan words have also long made their way into different languages, through loanwords tied to Mayan inventions.

Cigars and chocolate

When the Spanish landed on the coasts of the Yucatán Peninsula in the 16th Century, they found around a dozen Mayan city-states tied to a shared past but also facing deep divisions. Some Mayan rulers saw the arrival of the Spanish as an opportunity to settle old tensions and allied with the Europeans to crush their rival cities. Learning the languages spoken in the area was crucial for the Spanish wishing to maintain these new alliances. And, once the Peninsula was conquered, they used the local languages to evangelise, istrate and create a new society.

In his travels throughout the Americas, Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, the Spanish missionary, described a widespread local custom: "sipping" and "sucking" burning herbs. In Mayan culture, tobacco was smoked and drunk in rituals. The act of smoking those "dried herbs stuffed into a certain leaf", as de las Casas put it, was named siyar in ancient Mayan, which later evolved into the Spanish cigarro and, much later, into the English word cigar, to describe a roll of tobacco leaves.

Another Mayan word that slipped into other languages is cacao, the beans that make up chocolate and that de las Casas himself introduced to Europe in 1544.

Today, more than 30 Mayan languages exist and are spoken by at least six million people worldwide. Although some, like Chicomuseltec and Choltí, have disappeared or are close to extinction, others, like K'iche', Yucatec and Q'eqchi, have around a million speakers each.

They all come from the same language, Proto-Mayan, spoken before about 2000 BCE. They are so different from one another, however, that speakers of Mam, which has around half a million speakers, can't understand K'iche', and Yucatecans can't understand Mam. Of Yucatec, Aroldo says, "it's like German to me" – a language he doesn't speak at all.

Getty Images

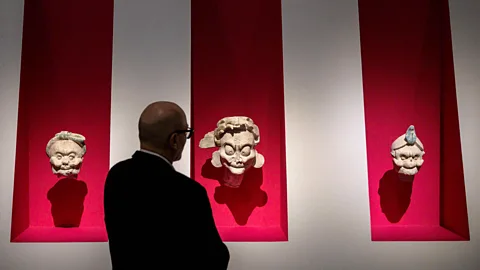

Getty ImagesFor nearly 2,000 years, Mayan languages had their own writing system, known as Classic Maya. Composed of hieroglyphs, it was only used by those at the top of the social pyramid. "If we want to make a historical equivalency, we can compare Classic Maya to Latin," says Llanes-Ortiz. "It was a prestige language. It was spoken by the elites, while the rest of the population spoke their own language that, little by little, mixed with Latin."

The Spanish missionaries deemed hieroglyphs pagan, and systematically purged them. The sons and daughters of the Mayan elites were forced to abandon hieroglyphic writing and learn to use the Latin alphabet, and most of the books written by that time, known as codices, were destroyed. But the oral languages were tolerated, and under a new robe – the Latin alphabet – have survived until the present day.

"The use of Mayan languages was so common and widespread during colonial times that community acts, balance sheets, wills, political declarations, memorials were all written in them, but everything was in Latin characters that remain in the archives of the city of Seville," says Llanes-Ortiz. "Even after Mexico's independence from Spain, Mayan languages continued to be used as lingua franca throughout the Yucatán Peninsula."

Western scholars began to study the Mayan hieroglyphs, long suppressed by the Spanish, in the 19th Century. While American and Russian linguists made significant progress in deciphering them throughout the 20th Century, Llanes-Ortiz says that huge breakthroughs were reached in the 2000s when Mayan scholars and speakers were included in the conversation. It was then that researchers understood that hieroglyphs represented not just complex concepts, but also syllables forming words.

The involvement of native speakers has advanced the study of Mayan languages, while inspiring a new generation of Mayans to reclaim hieroglyphic writing. Groups like Ch'okwoj or Chíikulal Úuchben Ts'íib are hosting workshops, and making t-shirts and mugs using ancient Mayan glyphs to resuscitate them and transmit them to future generations.

Mayan languages move north

Aroldo was five when he watched his first cousins leave San Juan Atitán for the US. He wouldn't see them again for years, but he listened to their voices on the cassette tapes they sent every now and then telling stories of a foreign land.

The first Mayans known to reach the US, Llanes-Ortiz says, came as part of the Bracero Program, which brought Mexican workers to replace Americans who left to fight in World War Two. But the largest waves came decades later, in the late 1990s and 2000s, when Latin American migration began to peak.

Guatemalans living in the US went from 410,000 in 2000 to 1.8 million in 2021, all coming from a country of only 17 million. Among these migrants are many Mayans who have settled in states like Florida and California.

"The first migrants went to the US, tested the waters and saw how you could earn real money. Then they told their Mam friends, who followed, and soon, they began pulling others," says Silvia Lucrecia Carrillo Godínez, a Mam teacher living in San Juan Atitán, speaking in Spanish.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMigration has transformed San Juan from a corn- and bean-growing economy to one reliant on remittances, much like the rest of Guatemala. Today, nearly one in five Sanjuaneros moves to Mexico or the United States for better-paying jobs. "Migration is what sustains our village," says Carrillo Godínez. "The advice of the Mam people in the US to those here is learn to add, subtract, a little Spanish and go to the United States. It's the only way to progress."

For decades, Mayan immigrants in San Francisco settled in the Mission District. But, as housing costs soared in the 2000s and 2010s, many moved to the East Bay, particularly the cities of Oakland and Richmond. "There is a direct line to Oakland," says Scott, the linguist. "When I go to San Juan Atitán, and people ask me where I'm from, I don't say the US or California; but I say Oakland, and they know exactly where I'm from."

Aroldo has found a local community tied together by Mam and Mayan traditions. They celebrate traditional events and festivals, and help each other through neighbourhood committees. Occasionally, he receives a WhatsApp message in Mam: At jun xjal yab' – someone is sick; or At jun xjal ma kyim – someone has ed.

Like many migrants, Aroldo sees his time in California as temporary – it’s a place to work until he can return to San Juan Atitán to build a home for his family. Although he still mourns his father and misses his family back home and the fog-shrouded mountains of his childhood, he finds solace in Mam.

"There are so many paisanos (countrymen) here that I rarely feel nostalgic. Language makes it harder to miss your land," he says. That's why he always reminds his nephew, who attends an English-speaking school in the East Bay, to speak Mam at home. "First comes Mam, then Spanish, then English," he tells him.

* The calculation for the Bay Area was made based on data from the US Census Bureau on the Hispanic population in the nine counties of the Bay Area and their country of origin.

--