'The one thing we're all afraid of is going insane' – Stockholm Syndrome and the art of hostage negotiation

Getty Images

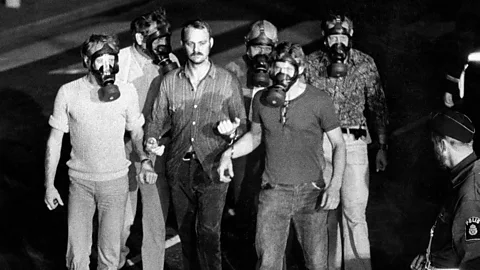

Getty ImagesThe six-day bank siege that inspired the controversial Stockholm Syndrome theory began on 23 August 1973. In 1980, a BBC documentary featured two pioneering New York police negotiators who had built their careers on the lessons they had learnt from hostage situations past, including this bizarre robbery attempt.

"But Sven, it's only in the leg."

Those were the words of Kristin Enmark, 23, who was one of four people being held hostage at gunpoint in a Swedish bank. It was day two of the siege, and robber Jan-Erik Olsson wanted to show the police he meant business by shooting her terrified bank colleague Sven Säfström.

Enmark told the BBC's Witness History in 2016: "Jan said to him, 'I'm not going to hurt any bones in your leg; I'm just going to shoot in the part that is not going to make so much injury'."

Looking back, she struggled to comprehend her callous reaction. She said: "In that situation, I thought that he was somehow being a coward, not letting himself be shot in the leg. I think it's awful for me to think that and to say that, but I also think it shows what can happen to people when they are in a situation that is so absurd. It is a situation that makes this moral shift. I really feel ashamed about this."

Although Olsson did not carry out his plan, Säfström later itted he had also felt grateful to his captors, and had to force himself to these were violent criminals and not his friends.

The term Stockholm Syndrome was coined in the aftermath of the siege by Swedish criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot to explain the apparently irrational affection that some captives felt for their hostage-takers. The theory reached a wider audience a year later when Californian newspaper heiress Patty Hearst was kidnapped by revolutionary militants. The 19-year-old appeared to develop sympathy for her captors, and ed them in a robbery. She was eventually caught and received a prison sentence. According to her defence lawyer, she had been brainwashed and was suffering from Stockholm Syndrome.

The art of police hostage negotiation was pioneered in the 1970s by New York cops Frank Bolz and Harvey Schlossberg. The idea came out of the botched rescue at the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were killed after being taken captive by of a Palestinian militant group. In 1980, Bolz and Schlossberg featured in the BBC documentary Inside Story: Hostage Cops and explained that the NYPD hostage negotiation team was set up because of fears something similar could happen in the city. Their aim was to safely de-escalate situations instead of going in Hollywood-style with all guns blazing. Delaying tactics gave hostage-takers more time to make errors, and created room to build rapport with their captives, making a violent end less likely.

By the end of the 1970s, about 1,500 police forces had sent officers to New York to learn from Bolz's practical experience of more than 200 hostage incidents. These lessons travelled even further when a BBC documentary crew sat in on a masterclass delivered by Bolz and Schlossberg, a former traffic cop with a doctorate in psychology. For Schlossberg, Stockholm Syndrome – or Survival Identification Syndrome – was not a complicated concept.

"We simply mean when two or more people get together, they form a relationship – that's all it is," he said. "Of course, the more stress in the situation, the quicker the relationship, and the more intense it's going to be. When people are in crisis, and they're not sure about what's going to happen, the one thing we're all afraid of is going insane. I mean, we're always worried about, are we losing our mind? Is this really happening to me? What am I doing in a thing like that? Am I experiencing this? And what we do is we want to test our feelings against another person, because if that person is sharing this experience and he's seeing the same thing, and he ain't going bananas and this is really happening, maybe it's OK."

Schlossberg said that while criminals would often put hostages on the telephone to speak to negotiators, there was no point trying to obtain secret information from them: "The hostage will tell the criminal everything you tell him. They make terrible witnesses and when they get released, the intelligence information they give you should be taken for what it's worth."

Bolz said that when hostage-takers made demands it was important not to dismiss them outright. He said: "You never tell him no, but you don't necessarily tell him yes. It's always, 'Let me see what I can do – let me try for you'."

Schlossberg said it was vital that police kept control of the situation, insisting that the hostage-taker "will talk to our negotiator or he talks to no one". "We don't want lawyers, mothers, priests – we don't want them talking," he said. "The fantasy is, you're going to talk to no one unless you get the person you want to talk to. The reality is, how long could you sit in this room and not make with the outside world">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });